Two eggs fertilized by two sperm coincided in a uterus and, instead of giving rise to two sisters, they fused to form a single person: Karen Keegan. When she was 52 years old, this woman from Boston suffered very serious kidney failure, but luckily she had three children willing to donate a kidney to her. The doctors did genetic tests to see which offspring was most compatible and they got a major surprise: the test said that two of them were not her children. The reality was even more astonishing: Karen Keegan had two different DNA sequences, two genomes, depending on the cell you looked at. Biologist Alfonso Martínez Arias maintains that this chimeric woman is conclusive proof that DNA does not define a person’s identity.

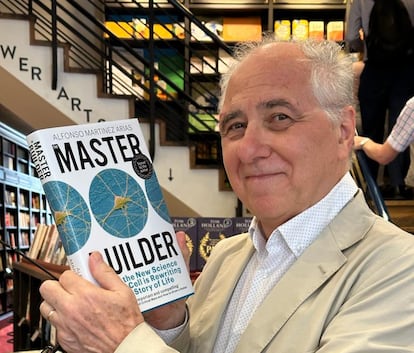

The most inspiring science book of all time is The Selfish Gene, according to a survey carried out by the Royal Society of the United Kingdom. In this famous work from 1976, British biologist Richard Dawkins defended that the DNA molecule uses the human being as a mere envelope in order to be transmitted to the next generation and become immortal. “We are survival machines, robot vehicles blindly programmed to preserve the selfish molecules known as genes,” Dawkins stated. Almost half a century later, Martínez Arias refutes this perspective of the selfish gene and proposes a much more romantic alternative: the altruistic cell. “An organism is the work of cells. Genes merely provide materials for their work,” he says in The Master Builder, a fascinating and provocative book from the London publisher Basic Books that will also be published in Spanish this year.

Martínez Arias, 68, argues that the DNA sequence of an individual is not an instruction manual or a construction plan for their body, but a box of tools and materials for the true architect of life: the cell. The Madrid-born biologist argues that there is nothing in the DNA molecule that explains why the heart is located on the left, why there are five fingers on the hand or why twin brothers have different fingerprints. Cells are what “control time and space,” he proclaims. They are the ones who know where right and left are, and where exactly a person’s foot or an elephant’s trunk should end.

The biologist spent four decades at the University of Cambridge, investigating how a solitary cell with a unique DNA sequence — the fertilized egg — is capable of multiplying and becoming an individual with billions of cells specialized in various tasks. “The question often arises as to how it is possible that such similar genomes can build such different animals as flies, frogs, horses and humans. However, the real wonder is how the same genome can build structures as different as an eye and a lung in the same organism. Let’s give the cells the credit they deserve,” says Martínez Arias, who in 2021 left his chair of Genetics at Cambridge to join Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona.

The scientist remembers the global surprise after the birth of the first cloned cat, called Copy Cat, on December 22, 2001. Her DNA was identical to that of a calico cat — white, orange and black — yet Copy Cat had white and tabby fur. The two supposed clones looked nothing alike. The researchers had copied the genetic information from a cell that had the orange gene inactivated. The American company that sought to enrich itself by selling identical clones, Genetic Savings & Clone, had to close down in 2006. “People didn’t want a cat with the same genes as their pet, they wanted a cat that was exactly the same and behaved in the same way,” notes Martínez Arias. “That is simply impossible.”

The researcher uses a legendary phrase from his British colleague Lewis Wolpert (1929-2021): “It is not birth, marriage, or death, but gastrulation which is truly the most important time in your life.” Martínez Arias compares this phase of embryonic development to a cellular dance with a perfect choreography. About 14 days after a sperm and an egg come together, the resulting ball, of about 400 cells, will begin gastrulation: a dance that lasts six days and ends with the tiny sphere becoming the first sketch of the individual. In this new 20-day structure, the three axes of the future person are already distinguishable: left and right, up and down, belly and back.

These first days of pregnancy are an enigma, due to the obvious physical and ethical barriers to directly observing the process, but Martínez Arias’ team in Cambridge overcame the difficulties in 2020 with an ingenious alternative. The Spaniard and his lab colleagues used a chemical cocktail to induce embryonic stem cells — derived from leftover embryos from fertility clinics — to form a three-dimensional structure similar to the result of gastrulation: a sketch of a person, but without the seed of the brain or the tissues that would generate the placenta. This historic advance was announced in Nature, a repository of the best world science.

Martínez Arias believes that these structures that partially imitate the human embryo, called gastruloids, “unequivocally show that cells are the masters of construction, and that there is no blueprint in the genome to direct what they do.” The biologist marveled, for the first time in history, at something very similar to what happens in a mother’s womb: a perfect choreography in which cells communicate with each other, through forces and chemical signals, and end up occupying their place as if they knew exactly what their destination was. “This ability to self-organize could be a fundamental property of cells,” hypothesizes the researcher, who cites the spectacular techniques of the French neurobiologist Alain Chédotal to visualize the cellular structure of embryos.

The Pompeu Fabra researcher notes that his colleague Susanne van den Brink discovered that gastruloids were only formed if a specific number of cells were used: about 400. Cells know how to count. If the 400 are not there, the dance of gastrulation does not begin. They all have the same DNA molecule in their nucleus, but each cell reads only a few sections, specializing in certain tasks. That is why a brain cell will not look anything like a skin cell, despite having the same DNA and descending from the same fertilized egg. “Gastruloids are proof that a confederation of cells has the ability to work together, interpret signals from each other and the environment and choose which genes to use and when,” says the biologist. “Genes are not our identity,” he repeats over and over again.

For Martínez Arias, the new science of the cell is rewriting the story of life. “We still don’t know much about how cells are organized to use the genome, but the answers are out there, starting to manifest in our embryo-like cellular wonders or organoids. The century that is already underway is, and will be, the century of the cell,” he proclaims.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition